Clothes Make the Volunteer

I’ve heard it said that, when the first Micro groups arrived on Yap after training for several weeks in Hawaii or Key West, they arrived at night. They got off the plane and found, there at the airfield waiting to welcome them, a crowd of Yapese carrying torches. There were songs and dances and greetings all around. And when those were over, the Yapese led the Volunteers by torchlight around the villages of the island, dropping them off, one by one, at the homes of the families who would be their hosts for the next two years. I like to think that there was much tuba-drinking along the way and that the slowly dwindling crowd finally ended up in Colonia at dawn, where the new Outer Islands Volunteers caught their first glimpse of the Yap Islander at its moorings, gently bobbing up and down on the calm waters of Chamorro Bay and gleaming in the first rays of the rising sun.

It’s a pretty tale, isn’t it?

I have no idea whether or not it's actually true.

What I do know is that, when the Micro 7 group, my group, of Peace Corps Volunteers arrived on Yap in 1968, things could not have been more different.

For one thing, we weren’t arriving after weeks of training in some glamorous locale; we were arriving after a few days of staging in Escondido, California. So dropping us off one by one in villages probably wouldn’t have been a good idea, unless the Peace Corps was aiming at total culture shock and a plane full of fledgling Volunteers on the next flight back to Guam, which thankfully it wasn’t.

For another, we weren’t arriving on some magical moonlit night, with doves cooing in the breadfruit trees and the heady scent of plumeria blossoms wafting up on soft breezes towards our nostrils; we were arriving in the middle of the day, under the full force of the blazing equatorial sun, and after a passing thunderstorm had left the humidity level hovering somewhere between 140 and 160 percent.

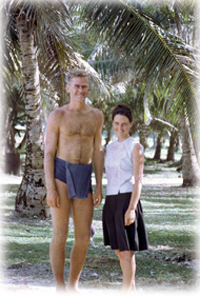

And for the final little bit of the ironic and the absurd, we weren’t arriving in any sort of clothing a rational mind would normally associate with twenty-somethings and the tropics. I don’t remember what the women were wearing (sundresses probably, or something like that), but I know for a fact that the guys were wearing shoes and socks, shirts and ties, and long pants and jackets.

We were dressed like that because we had to dress like that. It was decreed.

Apparently, the men in the group before ours had arrived on Yap looking so casual you might have thought they were getting ready to take a swim. There might even have been a photograph or two of them deplaning in sandals, shorts, and tee shirts that got just enough media play to bring them and their attire to the attention of the Trust Territory’s High Commissioner. Well, you can imagine the spate of cables, calls, and communiqués between Saipan and Washington that must have set in motion.

The result of the tempest in that particular teapot was that the Peace Corps issued a fashion edict, the brunt of which fell squarely (and unfairly, I always thought) on the unresisting shoulders of the Micro7 PCVs.

To be honest, I think the Peace Corps tried to couch the edict in the most positive terms it could, all things considered: the long pants, jackets, and ties were pitched as apparel that would enable us to show our respect for the Yapese. Never mind that the Yapese who greeted us at the airport were dressed far less, well, conservatively.

Thank God it was the end of the 60s, and the 70s were just around the corner. As we found our bearings over the course of the next few months, we started to see more clearly, and one of the things we saw more clearly was that edict for what it truly was: a small but telling example of a repressive society’s attempts to do what repressive societies do best.

So points for recognizing repression; no points for defying it.

At least not yet.

When the ceremony at the airfield greeting us Micro7 PCVs was over (and sorry we were not to see a small but dedicated band of UPI stringers hiding behind every bush and tree, aiming telephoto lenses at our sweat-soaked clothing, and snapping away for all they were worth), and we had been carted away to the high school so that training could begin in earnest, clothing sanity at last returned.

Or it did for the men: off came the suits and ties; on went the sandals, shorts, and tee shirts. In time, many of the men would even wear the traditional Yapese thu.

No one objected.

The women, however, faced more enduring constraints.

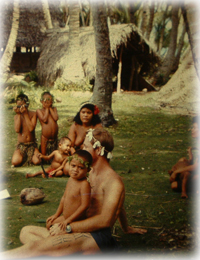

While politicians back in Washington probably wouldn’t have cared in the least if a Peace Corps woman wore shorts as she went about her daily work on Yap, she couldn’t possibly have done that because anything that exposed or drew attention to a woman’s thighs was highly offensive to the Yapese and, therefore, taboo.

At the same time, the Yapese wouldn’t have thought twice about that same Peace Corps woman’s walking around wearing nothing above her waist but a necklace—in fact, they might have thought it strange that she didn’t—but American politicians would have become apoplectic if that had happened.

Correction: I should have said, “American politicians became apoplectic when that happened.”

Because, God love ‘em, that’s exactly what some of those Peace Corps women on Yap at length did: they saw the double standard, they recognized the colonialist racism driving it, and they took off their tops in solidarity and defiance, becoming even better Peace Corps Volunteers in the process.

Well, that worked great for a time, and everybody was happy as long as there weren’t any American politicians around, or tourists with cameras who knew American politicians.

Eventually, of course, some wandering blowhard on a TT junket or some self-righteous busybody vacationing from Corpus Christi would visit the island and come across a topless Peace Corps Volunteer teaching in her school or dancing with a group of women from her village, and then all hell (or a very small part of it) would break loose.

When that happened, some of those Peace Corps women would go home, some would be shipped away to an Outer Island, some would stand their ground. Or try to.

All of them made you want to stand up and cheer.

You meet a lot of people in your time on earth, and some have characters and personal qualities you can’t help but aspire to. For my part, I’ve admired many people. But I don’t think I’ve ever admired anyone I actually knew more, certainly no one I know has made me feel prouder to be an American, than the women in those early Micro groups who showed their kinship with the women and the people of Yap by going topless.

Although, to my mind, the women of Yap always did look way better topless than the Peace Corps women did.

Hey! I’m just saying!

Maybe now would be a good time to change the subject.

The $50 wash-and-wear suit I bought at Sears before I got on the plane to Escondido, the suit I bought just so I’d be wearing “proper” attire the first time I got off a plane on Yap: I wore that suit only once, in case you're wondering.

When training was over and I finally moved to the village in Delipebinaw where I spent my first year on the island, I folded that suit as carefully as I could (okay, so maybe it wasn't so very carefully) and put it away for safe-keeping under the wooden platform on which I slept. And, while it was there, keeping safe (or so I thought), termites crept in and very silently, but oh-so relentlessly, devoured it.

I was never so happy in my life to see anything go.

Frank Glass

New York, NY

November 2005

Photograph by Art Hegewald

Click here to add text.

Photograph by Mike Lemont